TWO MOVIE VERSIONS OF ERNEST HEMINGWAY’S “THE KILLERS”

PREMISE: During and after World War II a technocracy was created in the United States, instituted via a collaboration between large corporations and government agencies which included the Defense Department and the Central Intelligence Agency. A 1948 novel which examines the beginnings of this process, set on an Army Air Corps base with glimpses of Washington D.C., is Guard of Honor by James Gould Cozzens. The novel shows how the growing military juggernaut enlisted outside talent of all kinds. “The Best and Brightest,” to use a term originally applied to John F. Kennedy’s advisors and cabinet when he took office in 1961.

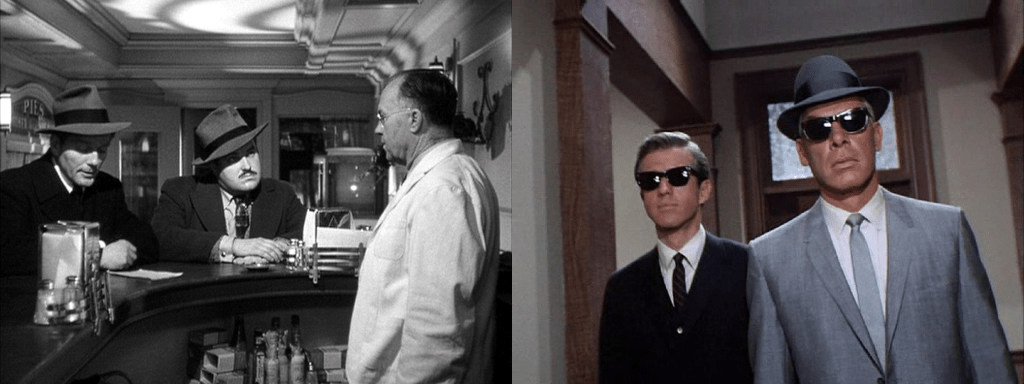

TWO film versions of Hemingway’s classic 1927 short story– the story considered a forerunner of hard-boiled fiction and film noir– illustrate the changing social and cultural landscape. A famed bigger budget version was produced by Mark Hellinger and directed by Robert Siodmak in 1946. The low-budget remake– originally meant as a television movie but rejected by NBC for its violence and released to movie theaters instead– was produced and directed by Don Siegel.

WHAT are the differences between the two films?

THE HIT MEN

In the 1946 version they’re sloppy and inefficient. At the climax, almost inept.

In the 1964 version they’re corporate; in appearance– their walk and expressions– robotic. In action, coldly efficient. The Lee Marvin character, “Charlie,” is as inexorable in carrying out his goal as Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character in The Terminator. His sarcastic sidekick, “Lee,” played by Clu Gulager, is even more sociopathic.

THE PLOT

In the 1946 version, the backstory to the murder is looked into by an insurance investigator earnestly played by Edmond O’ Brien.

In the 1964 version the investigation, and resulting plot conflict, is handled by the professional killers themselves, within the all-encompassing top-down technocratic system. As if they’re the de facto police department.

STRUCTURE

The 1946 movie has sloppier construction, with eleven flashbacks, which for a 103-minute film might be too many.

The 1964 flick, as with all Don Siegel films, is tighter, at 93 minutes and three flashbacks.

THE BOSS

In the first movie the heist mastermind/boss is played by Albert Dekker. In the remake, by future California governor and U.S. President Ronald Reagan, in his last movie part before entering politics. The role as the story’s villain reflects, perhaps, the real person behind the politicking. Too close of a parallel? Or not.

THE VICTIM

In 1946, Burt Lancaster plays the man gunned down, a former boxer. In 1964 the character– played by John Cassavetes– is a mechanic and race car driver. The difference between a viscerally physical sport with no mediation between contestants, no gadgets, and a sport built on the construction and manipulation of machines. Technology.

THE FEMME FATALE

Ava Gardner in the 1946 version is striking-looking and glamorous– but is she also more vulnerable than the scheming, hard-edged character played by Angie Dickinson in the remake? This might be a draw. Both are dangerous.

SETTINGS

The 1946 film is set in a pre-war world, like the Hemingway short story itself. Dirty, crude, inhabited by seedy diners and older, dilapidated buildings and interiors.

In color, with cleaner post-war sets– as clean as Hemingway’s prose– and better fitting, more precisely-designed clothes, the remake is as modernist as the burgeoning technocracy itself.

A BETTER EXAMPLE of mid-century modern design and thought in film– in every aspect of the work– is the 1967 John Boorman movie “Point Blank,” which also stars Lee Marvin and Angie Dickinson. This narrative takes the madness a step further. In a hellish, dystopian world, the corporation rules all.

CONCLUSION

TO TRULY UNDERSTAND neo-noir offerings like 1964’s “The Killers” and 1967’s “Point Blank,” one needs to put them into context as part of larger forces: societal, cultural, economic. The two movies reflect changes taking place in America which were intentionally transforming the country into something scarcely recognizable from the populist version which had existed before the war. Top-down institutional changes greatly affected American literature itself, including what kind of writing would become accepted and acceptable– a huge subject to be further explored. Possibly in an e-book?

-Karl Wenclas